I’ve made a small edit to my first post on Amazon’s recent changes to their sales algorithms. As you’ll recall, in that post, I took a look at the three different sets of popularity lists Amazon was displaying between March 19 and May 3. To summarize, List A was Select- and indie author-friendly. List B showed signs that making your book free would be drastically less effective than it used to be. And List C looked downright draconian: even strongly-selling indie books that had never been free were ranked 15-25% worse on List C than on List B.

Originally, we thought this was because List C factored physical book copies into its ranks, inadvertently penalizing indies who predominantly sell ebooks. We were wrong. The difference appears to be about price.

I first started looking into this after Phoenix Sullivan noticed there were very few $0.99 books high on the popularity lists. (The popularity lists are the main browsable lists displayed on Amazon. For instance, the Epic Fantasy list can be seen here.) It was theorized that the new algorithms were discriminating against the $0.99 price setting, weighing $0.99 sales at a lesser value than at higher price points. I wasn’t entirely comfortable with this theory, because I generally don’t think Amazon sets their algorithms with specific goals in mind (besides “Make $, win”). So I compared hundreds of books on several different popularity lists, focusing on the lowest-priced ebook titles. Soon, I was honing in on the highest-priced books, too. Because I was seeing something very, very strange.

The higher the price, the better the book was placed on the popularity lists.

In other words, say you’ve got a $0.99 book at #10 on the Epic Fantasy list. (Popularity list, not bestseller.) Say its sales rank (bestseller list) is #1000. The books at #9 and #11, meanwhile, are both listed at $9.99–and their sales ranks will probably look more like #3000, say.

This isn’t an ironclad correlation. Bestseller rank is a transitory thing. It shifts very quickly compared to popularity rank; a book that’s #1000 today could be #1 or #10,000 tomorrow. Seeing one instance of a book outperforming its bestseller rank on the pop list ranks proves nothing.

Seeing hundreds of these instances, however, is another thing altogether.

And that’s what I saw. Repeatedly. Undeniably. It was 1 AM, I’d had a couple of drinks, and my fiancee was snoring on the couch as I nerded it up with my numbers, but what I was seeing was strong enough to not only prove the theory I’d set out to disprove, but to go one step further: all things being even in terms of sales, not only did a lower price indicate a worse position on the popularity lists, but a higher price indicated a better one.

The implications for indie authors are immediate. And not pleasant. Most indie authors price their ebooks between $0.99 – $5.99. A few brave souls and small presses price as high as $9.99, but generally speaking, $5 and under is seen as the way to reach readers who may be hesitant to take a shot on a lesser-known or completely anonymous author. But if you price at $2.99 while HarperCollins prices at $12.99, you’re going to have to sell significantly more copies to be neighbors on the popularity lists. And if you’re selling at $0.99, you’re going to have to sell very, very well to achieve the same level of visibility.

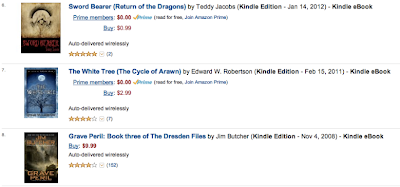

We’ve termed this change “price biasing.” Here’s what it looks like in practice. Let me show you a shot of the Epic Fantasy popularity list:

|

| Evidence of price biasing: Epic Fantasy popularity list, page 2 |

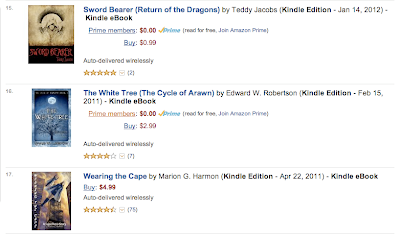

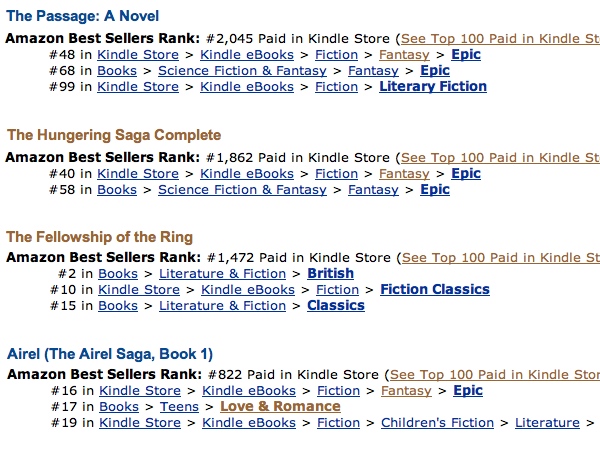

Now, here is the bestseller rank of these same titles:

|

| Bestseller ranks of these same books |

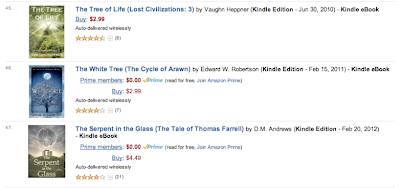

Let’s move to the next page:

|

| Epic Fantasy popularity list, page 3 |

And their bestseller ranks:

|

| Bestseller ranks of these same books |

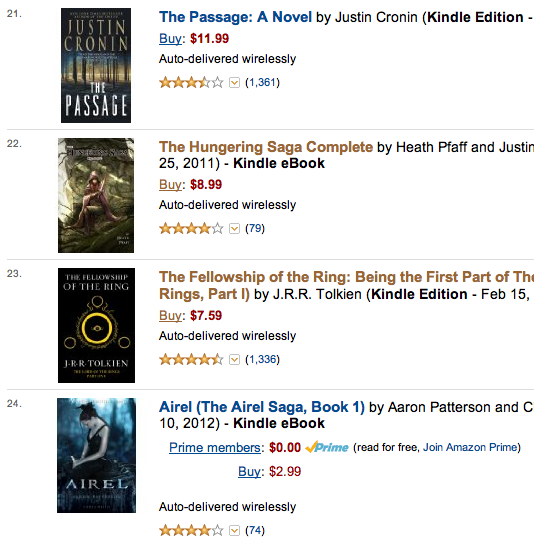

Take a look at that–in the first example, all of the higher-priced books shown are ranked above the lower-priced books on the popularity list, but their sales ranks are worse. In order! In the second example, the $0.99 book requires drastically higher sales to keep pace on the popularity lists with the $13.99 book. For another example of price biasing, simply go to the top of Epic Fantasy, where George R.R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones 4-Book Bundle, is priced at $29.99 with a bestseller rank of #60 and a popularity list rank of #1. The next book, Martin’s A Game of Thrones, is priced at $8.99, yet is #2–behind the omnibus–despite a bestseller rank of #27.

There are a lot of variables at play here. Because of the volatility of bestseller rank, I can’t be certain that the higher-priced books haven’t outsold the lower-priced ones over the last 30 days, and it will be easy enough to find counter-evidence where books are “properly” ranked and price seems to make no difference. But I’ve tried to minimize the variables by choosing books that haven’t been recently released (so sales should be steadier) and by going to page 2 and 3 of the popularity list, where the volatility should be lesser than at the very top. Really, it wasn’t hard to find this example. Because it’s all over the place. And if you look at hundreds and hundreds of titles next to each other on the popularity lists–especially the extremes, $0.99 – $2.99 books next to $12.99 – $29.99 books–the correlation is extremely high.

I don’t have the answers to a lot of the inevitable questions. I don’t know what the “ideal price” would be to take advantage of this new formula. I don’t know how many more copies you need to sell at $0.99 to achieve the same weight as you would selling at $9.99. I don’t know why Amazon did this, particularly when they price their own imprints at $7.99 and under. I don’t know if this is the end of the world or a brief couple weeks of suffering followed by another golden age.

And let’s not storm the gates or raise all our titles to $199.99 just yet. The popularity lists are far from the only driver of sales through Amazon. There are bestseller lists. Targeted emails. Bargain book lists of all shapes and sizes which you’ll only make through pricing lower. And if you raise your prices significantly enough to achieve a major change on the new popularity lists, you may drive away so many sales your placement actually winds up going down. Unless you’re priced at $0.99, I don’t think raising your price by a dollar or two will make any real difference to your placement on the popularity lists, so please don’t overreact–if you’re still selling, you’re still selling, no matter how the new algorithms may work.

Still, I don’t see how these new lists are any good for indies under any circumstances. What they do is force us to sell more books to maintain the same visibility as higher-priced trad titles. They diminish our ability to experiment with lower prices, whether the goal is a temporary sale, a low-priced entrypoint to a series, or because you just don’t feel comfortable charging more than $0.99 for that 5000-word story.

Furthermore, the playing field is no longer level. Indie authors published through KDP only earn 70% royalties at prices between $2.99 and $9.99. Yet many traditionally published books that are most benefiting from price biasing are priced at $12.99 – $14.99, with some omnibus editions priced as high as $22.99 – $29.99. If indies want to match those prices to match their visibility on the popularity lists, they’ll actually make less money with each sale than they would at $9.99. There’s no way to win.

I don’t like fearmongering. But I don’t see how it helps to sit on this information any longer. I encourage you to look at the popularity lists for yourself. Maybe I’m wrong. I’d prefer if I were. I’ll try to answer any questions in comments, but be prepared for a lot of “I don’t know.” All I know for sure is that if this analysis is correct, the deck has been stacked against us. I highly doubt it was intentional. Indies aren’t being targeted. We’re just a small part of the Amazon equation, and as Amazon attempts to maximize their revenues, I really don’t think they care who that revenue’s coming from. And remember: this is just one factor among many, many others as to how a book is seen on Amazon’s storefront. It’s not a revolution in and of itself.

But it does feel like it will have some impact on indie authors. I thought it was time to share and let everyone experiment for themselves.

So not 12 hours after my post about how Amazon’s algorithms work, Amazon changed their algorithms again. This is a big enough deal they apparently just caused me to quote Britney Spears.

Fortunately, the latest changes weren’t a complete revolution. By all accounts, there is once again a single list seen by all customers. I’m not sure exactly how this new list works–the Avengers are still working on it–but it seems to hew very closely to one of the lists we already understood. And if you are a Select author who leans on free giveaways for sales, here is my current advice to you:

Sorry, couldn’t resist. I actually don’t think we should flee the battlements just yet, for reasons I’ll get into lower down, but this is bad news for Select authors. Phoenix Sullivan has alluded to this, and will surely have more to say herself, so keep watching. Anyway, cause for panic: the new list looks an awful lot like List B. As a refresher, here are the main mechanics (that I am aware of) for how List B works:

- Ranks are determined by the last 30 days of sales, with no extra weight given to the most recent sales

- Free book downloads are discounted heavily–maybe as little as 10% the value of paid sales

- Borrows don’t count as sales

I’m not sure about whether borrows count or not on this new list. Won’t have the data on that front for a while. I am positive free books are counted, and that they’re counted at a discounted rate–feels like 10-15% of a sale. (In other words, for every 10 freebies given away, you’re credited with 1 sale for the purposes of pop list rank.) You can see this for yourself by trolling the popularity lists. You’ll see a few titles that are permanently free scattered across the first few pages. If freebies didn’t count, you wouldn’t be seeing them on the lists at all, and if they did count, you’d see a lot more permafree titles and Select titles higher up on the lists.

Also, if a book has fewer than 30 days of history behind it, as in it’s a new release, that doesn’t seem to be counted against it. Seems like the pop lists will just count however many days it does have on its record.

What does this mean, then? Well, for starters, it’s probably the end of the 3-day bump. This was the term coined on Kindleboards for sales on Select titles that had recently been free. In the past, List A would update roughly 40 hours after your book reverted to free. It counted freebies to sales at a 1:1 ratio (or very close to it) and weighted a book’s last few days of sales very heavily. So if you went free and gave away 5000 books, in the afternoon two days after your promo ended, your book would be credited with 5000 sales, vaulting it to the top of the “most popular” lists. With your book in front of so many customers, you’d see a lot of sales, spiking late on Day 2 and carrying through Day 5 or so as your rank decayed and your book was pushed down the lists by new titles rolling off free.

I don’t think that’s going to happen anymore. For one thing, List B isn’t weighted toward your last few days. It seems to take an average of your last 30. That levels the playing field for books that have been selling steadily for the last month while largely ignoring sales spikes that don’t prove to be lasting. For another thing, when you come off a giveaway of 5000 books, you’re no longer credited with 5000 sales towards determining your pop list rank. Instead, you’re credited with something more like 500. Possibly 750, or even 1000–I’m not sure just what the conversion rate is–just that it’s definitely a lot worse than 1:1.

If you don’t get credited with sales, you won’t vault up the pop lists. If you don’t vault up the pop lists, you won’t be seen by customers. If you don’t get seen by customers, you won’t sell books.

Does this mean those of us in Select should flee from the incoming flood of orcs? Perhaps. Everyone loves a good stampede. But even if the three-day bump has departed for the swift shores of Valinor, freebies aren’t worthless. Giving away a whole bunch of books still means you’ve got your book in the hands of a whole bunch of readers. I hear word of mouth is a thing. While your book’s free, you’ve got tons of attention, meaning some of that attention will bleed over to your other books–especially if it’s a series. If you don’t have a built-in fanbase eagerly awaiting your next release, it might be a viable strategy to put it in Select, make it free right away, and get it some alsobots to help prop up early sales and build a little bit of what the kids call buzz. Furthermore, if you give away just an amazing amount of books, it may still be enough to pull you some decent visibility. Even if you can’t make page 1 of the pop lists anymore, there would be value in using freebies to push yourself up to page 5.

Also, this is just how things look right now. As should be obvious, Amazon changes how they do things all the time. They are wise. They want to make money. If they still want Select to succeed, at some point they will do something to help it, either by changing the algorithms again or by adding new perks to the program. What we’re seeing now will probably be completely irrelevant in another month or three or six.

It should further be noted that I don’t have the algorithms worked out to a T. I know what I’ve described here is incomplete. With the help of the Avengers, I hope we’ll know more soon, but let me stress this: I don’t know everything. I could be wrong about some parts of this or about all of this. I could be a brain in a jar dreaming that Amazon just screwed me!

But I’m pretty confident about what I’ve laid out here. Confident enough to make it public. For those of us who’ve been leaning on Select to sell books, the next few weeks or months could be lean ones. Plan accordingly.

UPDATE: The same day I posted this, Amazon changed their sales algorithms again. This post will provide a lot of the background to what I talk about in the followup post.

BACKGROUND

Around March 19, Amazon changed the way they sell books. In a Kindleboards thread devoted to the subject, authors tracking the performance of books during and after a free promotion began reporting strange results. Prior to then, books that gave away several thousand copies during a promo would shoot to the top of the popularity lists some 36-48 hours later. It was like clockwork. Clockwork that paid you several hundred dollars.

Because the popularity lists are a big deal. These are the default book listings you’ll see when you’re browsing around by genre. Here’s the Fantasy list, for instance, with GRRM clogging up the top 10 like the greedy goose he is. If you could ride a free promotion to the top of those lists, your book would be extremely visible to shoppers. Depending on genre and your book’s presentation, topping the pop lists could snag you dozens or hundreds of sales before other books overtook you. Sometimes that visibility was enough to launch a book into the stratosphere, where the stratosphere is also made of money. It was kind of a big deal.

Then, things changed. Except they didn’t change. Not for everyone. Authors began reporting lower sales than expected as well as strange-looking lists. Chaos reigned! Dogs and cats living together, watching couch-bound authors tear out their hair. After a couple weeks, we thought we had it figured out: there was no longer a single popularity list. There were two, and books no longer seemed to be vaulting to the top no matter how many free copies they gave away.

Well, we were wrong. There weren’t two lists. There were three.

Because I am extremely imaginative, I’m going to refer to them from here on out as List A, List B, and List C. I’ll get into the methodology in a bit, but for now, I worked this out through carefully observing my books, reading other Kindleboard authors’ results obsessively, and lobbing theories around with other authors. I would never have figured this out on my own. I know, never say never. Trust me, eventually I would have gotten frustrated and left to play Mario Kart instead. One other author in particular did tremendous heavy lifting. Like the Eye of Sauron, he (or she?!) is far-seeing and awesomely powerful. And much like Sauron, you can’t invoke his or her name without facing terrible wrath. Some of the Eye’s secrets must remain just that.

But the outcome of that info can be revealed. So without further ado, here’s how the three lists work.

THE CHANGES

List A is the same version of the pop lists that existed prior to March 19. It is Select- and freebie-friendly. Here’s roughly how it works:

- Ranks are heavily weighted to the last few days

- Free book downloads are weighted equally with paid sales

- Borrows count as sales

List B appears to be a throwback pop list, one that was running throughout most of last year. Here’s how book ranks are calculated on it:

- Ranks are determined by the last 30 days of sales, with no extra weight given to the most recent sales

- Free book downloads are discounted heavily–maybe as little as 10% the value of paid sales

- Borrows don’t count as sales

List C is a lot like List B, with a couple major differences:

- Free book downloads aren’t counted at all

- Recent sales are weighted somewhat more heavily than List B(?)

- Borrows don’t count as sales

What does that mean in practice? A lot. A lot a lot a lot. Here’s where my book The White Tree ranks on all three lists at this moment in time. Each shot will look a bit different because they’re taken from different browsers–that’s one way to see different lists. The list in question is Fiction > Fantasy > Series, a fairly quiet little fantasy subcategory.

List A:

List B:

List C:

Pictured: Oh shiiiiii–

METHODOLOGY

Most of this was achieved through comparing tons and tons of different books on different browsers, just like the screenshots above. Here’s some stats for the book in question that helped me figure out what was happening here. On March 28-29, The White Tree was downloaded 4700 times (free). On April 17, it was downloaded an additional 1300 times. In April, its paid numbers came in at 210 sales and 46 borrows.

Since March 19, my main browser’s been displaying List B. My big clue to List B came on April 28, when I noticed my book had, over the span of a day or two, dropped from #67 in Epic Fantasy to #165. Rank didn’t slide–it instantly dropped off a cliff. Why? Because it had been 30 days since all those free downloads had come in. I’d noticed the same thing around March 23–I’d done a huge giveaway February 22-23, and once 30 days elapsed, it suddenly plummeted from around #45 to around #255. I didn’t know what it meant then, in fact I don’t think I even knew there were two lists at that point (let alone three), but when it happened again, I had a pattern.

I also had several weeks of observations piled up by then to help me understand new data. For weeks, List B had been showing me very static lists. The books at the stop stayed at the top. There was very little churn. There were very few Select books, i.e. books that were likely to have recently been free, especially within the top ~60 results (first five pages). Most books at the top were traditionally published. List C was even more trad-dominated; generally speaking, an indie title on List B would be ranked 15-25% worse on List C if that title hadn’t been free, and would rank much, much worse if their List B rank was dependent on free downloads (like, hundreds of places).

When I compared the top 240 titles in Epic Fantasy between List B and List C, here’s what I found: on List B, 188 titles weren’t in Select, and 52 were. On List C, 217 titles weren’t in Select, and just 23 were. With no benefit from freebies, and with fewer paperback sales to pad the numbers, most indies get killed in List C.

When it came to figuring out that borrows weren’t counted in List B and C, The Eye of Sauron was particularly helpful. We compared Select books with lots of borrows to non-Select books whose sales were roughly equivalent to the Select books’ total sales+borrows. On List B and C, the non-Select book came out ahead by a good chunk. We compared Select books with lots of borrows relative to sales with Select books with few borrows : sales. (None of these books had recently been free, which acted as a “control” between List A and B.) The ones with a higher ratio of sales : borrows almost always came out better on List B than on List A.

While I wouldn’t lay my life on the line for every one of these observations, I am very confident in the overall conclusions reached. There are three different lists. You can see them for yourself–just compare lists on different browsers, computers, and Kindles. If you’ve gone free recently, you’ll note your popularity rank on List A is much better than B or C.

How do you tell which list you’re looking at? Well, that could take a day or three to figure out, but in short, if you see a bunch of Select titles on the first pages of the pop lists, you’ve probably got List A. If it’s almost all traditionally published books, it’s List B or C. From there, compare your lists on another browser/device; if you’re seeing List C, trad books will generally be even more dominant.

WHAT THIS MEANS

What does all this mean? Hey, maybe you haven’t noticed, but this post is already epically long. The internet is only so big, you know. I’ll save that for a future post. For now, here’s what’s key: there are three different lists. Your book is listed on all three, but any given shopper is only seeing one version of the lists. (In other words, different people see different lists.) If you’re an indie in Select, one of these lists is good. The other two? Well, let’s just hope they’re not here for too much longer.