Much like punching a crocodile, indie publishing is simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying. Exhilarating, because hey, you hit “publish” this morning and perhaps tomorrow the next thing you will hit is the ceiling after you discover you sold a million copies overnight. At the very least, it is exhilarating because you’ve taken control.

At the same time, it is utterly, skin-grippingly terrifying, because it’s such a big, big world, and when there are 1,504,243 titles and counting in the Kindle store alone, who the hell knows how a book ever sells a single copy in the first place.

When I put my first book out, I didn’t have the faintest idea what to do with it. Joe Konrath said I should join Kindleboards, so I did that. I posted about my book there and nothing happened. When my next books came out, I did the same thing, and more nothing continued to happen. It took me a full 12 months before all that nothing began to turn into something.

If I were starting my indie author career over right now, if I had my first book all ready to go out and conquer the world, here’s what I might do instead.

First, I would price my book at $2.99 or $3.99. This is not based on scientific research over here. But $0.99 is gaining a stigma and, from what I’ve absorbed elsewhere, $3.99 is the lowest price at which many readers will impulse-buy. When you’re just starting out, you’ve got nothing. No reviews. No also-boughts pointing back to your book. No recommendations from a reader’s trusted friend. There is nothing to break down a buyer’s resistance to buying your book, so you want to keep that resistance as low as possible with a bargain price. $2.99-3.99 seems to be low enough for that resistance to frequently be overcome by no other tools than your cover, your concept, and your sample.

Second, I would enroll my book in Amazon’s Select program.

This is a controversial decision. Well, it’s not that controversial. It’s about as controversial as all the thrillers listed on Amazon with subtitles including the word “CONTROVERSIAL,” which is to say that a few of us nerds might care, but nobody else gives a damn. Anyway, there is a mild controversy around Select. A lot of writers don’t like the idea of being exclusive to Amazon. A lot of writers think giving away your book devalues it and all books, and that it leads to temporary, inorganic gains that will soon dry up and blow away. What these authors are after is a long-term organic strategy of distributing to as many markets as possible and building up many different revenue streams that add up to a steady and sustainable income.

Well, good luck, guys.

That’s a little snarkety. But the thing is, every storefront presents you with a different set of tools to get your book in front of readers. And Amazon’s Select program is the very strongest tool of them all.

Quick aside: you should probably attach the phrase “In my opinion” to every sentence here. It will save us all a lot of time and anguish.

But here are some facts, or at least the facts as I have experienced them. If you push your book to Barnes & Noble, it will appear on the new releases list if readers sort by date, and there may be a week or two in which people see it. If you distribute to iTunes, it may not show up anywhere at all. Same with Kobo. It will be visible on Smashwords’ new releases for about a day before it’s buried, and then people are going to have to search for it to find it.

In other words, the window for your new book to take off purely organically is about 1-7 days long. If those 1-7 days pass and you haven’t sold enough to start making bestseller lists and generating also-boughts and all that–which you won’t–your book will be buried by all the new releases.

And that is where Select comes in.

For the record, I’m not an unrepentant Amazon/Select cheerleader. Of my 9 titles, only 2 are currently in Select, and I might not leave them there for another term. The program is not what it used to be. And it’s not a magic bullet. But it still has its uses.

Let us say you have hit “Publish.” Your book goes live. Shoppers can now find it by browsing the new releases or by searching for very specific terms and keywords, where your book will probably be listed as the #1,387th result. How else do you get readers to see your book?

One method, popularized widely by Amanda Hocking, is to submit your book to book bloggers. These people will review your book and then share it with their readership. This is a free and relatively simple way to get your book in front of people. But there are a lot of problems with this process. Another preface: book bloggers are great. I’ve known some spectacular people in the field who have really brightened my day with their devotion to finding new books and their enthusiasm in sharing them.

But you can’t count on book bloggers as a release strategy. They are overwhelmed with review requests. It may be weeks or months after you write to them before they can get to your book. If you’re chummy and entrepreneurial enough, maybe you can send them an ARC and schedule a review for around the time of your book’s release, but that means you have to wait to release until they’re ready, and waiting to release sucks. Anyway, that’s assuming the review will be good, which is no sure thing, even if your book is a professional product. Their opinions are highly subjective, after all. I’m a movie reviewer. A paid one who works for a newspaper. I hate all kinds of professionally-made movies that other people love dearly because reviews are nothing more than opinions, which always, always vary.

To summarize, then, reviews from blogs are likely to be slow to arrive, there’s a chance the review will hurt your book (just try selling it when it’s got a single two-star review), and even if the review is positive, the blogger’s audience probably won’t be all that big. If everything breaks right, it might be good for a few sales. Having a positive review out there may also help future shoppers decide to purchase your book. Seeking blog reviews isn’t a dumb thing to do, then, and it can help build up your long-term infrastructure, but it’s not going to do much for you on Day 1.

Anyway, things are different from when book bloggers gave Amanda Hocking the push that helped break her out. They’re all overwhelmed. You can’t hit enough of them to make much if any difference. Personally, the entire submission process feels too much like the agent hunt. I don’t submit to book bloggers anymore. Unless you write in YA, where they still seem to have some influence, I wouldn’t burn too much time on that route.

What do you do instead? It’s probably worthwhile to get your book listed on GoodReads. I am not intricately well-versed in how Goodreads runs, but if you have librarian status, or know someone who does, you should be able to add your book easily. If you can’t, it’s no big deal–someone will get to it eventually–but Goodreads seems to be a fairly important part of developing your book’s infrastructure, a concept I’ll get to in a bit.

But perhaps the most important thing you can do after hitting publish is this: make your book free. Right out of the gate. Give away the hell out if it. Schedule it for a two-day run, sit back, and see what happens.

“What happens” probably won’t be much. I think it’s vitally important to set the right expectations at this stage, and for most beginning authors, the reality is you’re going to sell very little right off the bat. In concrete terms, you’re doing very well if you’re selling 1/day. Many brand-new books from first-time authors with no platform can easily go days or weeks or even months between sales. A month from now, your sales column might consist of a number between 1-9, and that is perfectly okay.

At this phase, that means every single sale is a success. Every sale means someone stumbled over an unknown book and thought it looked interesting enough to pay money for. Do you know how hard it is to make that happen? Remember: 1,504,243 ebook titles and counting. As a brand-new book, the only place you’re showing up is in the new releases list and in keyword searches, and even then, anyone who found your book is either obsessive or almost superhumanly dedicated to finding new books, because they probably had to dig through dozens of pages before they happened upon yours. In terms of its present visibility, your book may have a “Buy” button on its page, but in many ways it still hasn’t really been published.

So cheer every day you do get a sale, but try not to be surprised or disappointed when you don’t. It’s probably going to be some time before your book starts traveling down some of the main avenues to discoverability.

And that’s why we’re going free right off the bat–to try to kickstart a couple of these avenues.

Again, don’t expect much from your first free run. A few hundred downloads on your first day is a pretty good outcome; my brand-new novels have typically pulled 200-500 on their first day free. If you’re in that range, hooray! I’d let it run free for a second day just in case it wants to catch fire, but it’ll probably give away fewer copies than it did the day before, which is perfectly normal.

Let’s address the exceptions real quick. If your book does start giving away a ton of copies–I dunno, 2000 or more–I would definitely add a third day, and keep adding days for as long as it keeps getting downloads. If it gets very few downloads–like, 50 or fewer over those two days–take a close look at your book’s presentation, its cover and blurb. If they look good, maybe you just ran into some bad luck, but this could be a sign that your book’s appeal isn’t quite there yet. One of the collateral benefits to making your book free is it can help you ballpark its overall sexiness. If you’ve got doubts about your book’s surface appeal, take this opportunity to fix it up now. Seriously. It matters.

If your book had a more middle-of-the-road outcome, though, and gave away 300-1000ish copies over its run, awesome. With a little luck, its infrastructure is about to get going. “Infrastructure” is just some crap I made up, but I think of it in terms of all the things about your book that makes it visible and makes it pretty. This includes any number of things. Reviews–onsite, on Goodreads, on blogs, wherever. Alsobots, which is our very clever slang term for the similar/related books a website will recommend to people viewing a specific title. Nice placement on lists (bestseller, popularity, new releases, whatever). And the ever-popular, ever-nebulous word of mouth.

By going free and giving away several hundred copies of your book, you’ll generate a bunch of alsobots that appear on other titles’ product pages that point back to your book. Hooray for visibility! And with a little luck, you’ll pick up a few Amazon reviews in the next few days and weeks, too. Maybe just one or two or three, but assuming they’re generally positive, these are going to help take advantage of your increased visibility by helping to convince anyone browsing your page that a living, breathing, non-you person enjoyed and recommended your book. (Because a real person did enjoy it. Don’t fake reviews. It’ll come back to bite you.) People might start reviewing your book on Goodreads, too–they’ll probably be more inclined to do so if its page already exists–which means their friends will see their reviews, which might entice them to check out your book. (More expectations-setting: Goodreads reviews are generally much harsher than Amazon. On Goodreads, 3 stars generally means they liked it. Didn’t love it, but liked it. That’s more like a 4-star review over on Amazon.)

You may wind up with a handful of sales in the first few days after your free run, too. Always an awesome feeling. These will probably slow down all too soon. But between alsobots (hopefully!) and reviews (hopefully!), maybe instead of selling 1/month, you’re selling 1/week. Or instead of 1/week, you’re up to 1/day.

These are small gains. Frustratingly small, probably. Well quit whining, whiner! Ha ha, sorry. But really, right now, every gain is a gain. And there’s a less-tangible gain going on here, too. Through this process, you are learning. At least you better be learning! Again, sorry. You’re learning how to sell books in general and how to sell this book in specific. That’s going to make this whole business much easier down the road.

For now, that’s it. I mean, if you want, you can tweet and blog and Facebook and pursue book bloggers about your book. That could help. It’s probably better than nothing. It makes me feel like a jerk, though, and it’s very time-consuming, so I don’t do any of that stuff. Except blog here. Because I enjoy it. That is the real secret to self-promotion: find what you like, and do that.

Otherwise, there’s not much more you can do for now. Watch your book for 2-4 weeks. Most of all, you’re looking for reviews. You’re going to want 5+ of them, ideally with an average of 4.0 or better. Having done a giveaway is risky at this early stage, because a couple of poor negative reviews right off the bat can turn this process into an uphill slog, but I think it’s worth the risk. Just be aware that this could happen.

Hopefully you can get these initial mostly-positive reviews just through your giveaway and through normal sales, but if they’re not coming, you may want to spend time actively pursuing them. Again: please be ethical. Sockpuppets stink. Paid reviews are against Amazon’s policy, too. Don’t fall prey to temptation. This is a game of patience. This won’t be your only book, right? Then act with the same class you’d like to be known for in a year or five or twenty, when you have many books and many fans.

While you wait, work on your next novel. Learn more about the business by reading blogs or Kindleboards or whatever. Try not to obsess. Almost everyone sucks at first. Like I said, it was a full 12 months before I started selling more than 5-20 books per month.

What you’re gearing up for here is your second giveaway. A giveaway with a much better chance to hit it big and push your book up to the next plateau.

A giveaway which–cliffhanger!–will be the subject of my next post.

So when we last left off, Breakers‘ free days had rolled off its popularity list rankings. That process took three days to finish (since it had been free for three days). Within a week, its sales had dwindled from 50-70/day to 10/day. I still had decent pop list placement, because it had sold so many copies in the last 30 days, but as each day passed, its pop rank continued to slide, because the old high-sales days were being replaced by new low-sales days. The end was night.

All the while, I was having a pretty obvious thought. If a big free run had propped it up in the first place, what if I did another free run? I probably couldn’t match my previous total giveaway numbers, but if I made it free while it still had a lot of paid sales credited to it, would that be enough to boost me back up the lists and continue the ride for another thirty days?

Meanwhile, I was having a second, far less reliable thought, because my brain can’t leave well enough alone. The thing is, Breakers was outselling a lot of the big sci-fi books around it on the pop list. Its bestseller rank was consistently better than Ender’s Game, for goodness sake. If the pop lists were calculated purely by sales, it wouldn’t have fallen off at all. The only reason it did drop relative to these other books was because they were priced higher, and ever since the beginning of May, price is weighted heavily in how the pop lists are ranked.

So what if I raised the price, too? Before, I was selling at $3.99. Would my sales hold steady (or close to it) at, say, $5.99? If so, when my latest free run ran out in another 30 days, would I be able to avoid eating cliff? Or at least suffer a less painful, more gradual decline?

So I set it free again. For two days. That was all the days I had left. And I waited to see what would happen.

And then Amazon botched my promo.

Instead of starting on June 23rd as scheduled, Breakers didn’t wind up going free until around 2 AM June 24th. I emailed KDP and called AuthorCentral (KDP has no phone number), but KDP was no help. That left me with just under one day to get as many downloads as I could. When it finally did go free, things went about as well as I could have hoped–POI picked me up, and so did ENT–and I finished the day with about 5600 downloads. On the one hand, that was really good, but on the other hand, with another day, I probably would have finished with between 8000-10,000. I needed every one I could get to restore my lost placement.

In the end, it wasn’t quite enough. I bounced back up the pop lists, but not as high as before. Initial sales were pretty good (25-30/day), but even at the higher price, it wasn’t enough boost to keep up with the higher-sales days of 30 days ago that were continuing to roll off my rank. I think my worse bestseller rank was hurting me here, too, but it’s really hard to say. Sales held steady for about ten days, then halved after July 4.

Since that end of the experiment was a bust, I decided to learn what would happen if I raised the price to $7.99. Interestingly, sales held steady around 10/day for another couple weeks. Three weeks out, they halved again. A few hours ago, Breakers ate cliff again, falling from #27 in Science Fiction > Adventure to #113. I’m guessing its sales are going to be pretty slow from now on. (Well, until more magic happens, anyway.)

For all I know, the higher price crippled its ability to stay as sticky this time, too. But I don’t think that’s the only factor. Over the last couple months, I’ve watched several books try this same trick–doing regular free runs to prop up their pop list rank for another 30 days. Every time, they don’t come back as strongly as before. Don’t get me wrong, they still do very well–coming back at #1500 instead of #500, say, or #2200 instead of #1500–but there is, in this limited sample size, a clear trend of diminished returns.

What’s happening? Are these books, including Breakers, slowly exhausting their audiences, even with similar pop list placement as before? Is it the case that, after an initial giant free run, a book is essentially experiencing what it’s like to be a popular new release, and when it pops back up after its first cliff, it’s being met with a lot of eyes that have already seen it?

Likewise, these books’ second and third big free runs are never as big as their first. Not that I’ve seen, anyway. The obvious conclusion–which isn’t to say the correct one, necessarily–is that they’re draining the well, so to speak. Massive free runs depend on just a handful of sites. Once you’ve tapped those sites once, the well has that much less water in it the next time you return. It refills over time as new subscribers sign up, but in my observation, it doesn’t refill completely within 30 or even 60 days. In fact, it may take much longer than that.

We’re back in the realm of speculation now. But the logical conclusion is this that riding free runs every 30-40 days can be an effective strategy (although ENT now says they won’t mention a book within 60 days of the last time it was free, meaning you’re basically down to POI, FKBT, and paid ads for exposure). This can last for several months, anyway. But it appears to be less effective the more you do it, and there is a point where a diminished 30 days of sales + a diminished free run isn’t going to be enough to prop you up to a significant place on the pop lists. When that happens, the run’s going to be over for a while. At least until the wells refill. Or you discover some other way to get your book back up there.

There’s also the question of whether giving away that many books might hurt your long-term sales. I have no answers to that question. People are buying their first ereaders every day. Considering there are already millions of Kindles out there, giving away 50,000 copies of your book over the course of a year may be a drop in the bucket of your potential audience. Readers aren’t a nonrenewable resource. Still, I don’t think it’s an unreasonable question, especially if you might be better served waiting to reach those readers for when you’ve got the next book in the series ready, say.

This is getting far afield. Nearly three months after the new algorithms spraing into being, here are my conclusions, which may or may not be remotely accurate:

* The Select program continues to reward far fewer books in the past

* The few books it does reward are well-positioned to continue to exploit their appeal

* If timed right, and with the right luck, these books can chain several months’ worth of strong sales together

* However, there will likely be diminishing returns after two or more of these runs, and it is unlikely to be something that can be maintained for more than a few months in a row

* While Select may no longer be very useful for most single titles, it continues to be quite useful for series

As for me, I’ll be leaving my fantasy series in Select for the time being, but I’m letting Breakers‘ Select contract expire early next month. I’d like to explore the other storefronts with a book I know is capable of selling. I’d like to see if I can build sales that are less roller-coastery. And to be perfectly frank, I’m pissed off at Amazon’s shitty customer support (grumble grumble bitch&moan). I’m sure they will be devastated to have lost my exclusivity.

What might this mean for your book? That is virtually impossible to answer. Maybe you’ll strike it rich on your next free run, but the chances of that are pretty low, unfortunately. And the strategy discussed above certainly isn’t a long-term plan (although giving away and selling that many copies may build you a readership that is very long-term indeed).

At the same time, what’s the alternative? De-enroll from Select, push the book to all the other stores, and pray it catches on? That’s not exactly an active strategy. Yet the other stores don’t have the same kinds of tools for discoverability that Select provides. It’s possible to make books free on iTunes and Kobo, yes, but that doesn’t result in the same list placement going free provides on Amazon. (Well, it kind of does on iTunes, but it’s clumsier, it takes much, much longer, and it’s far from guaranteed.)

In other words, we’re still in the same boat we’ve been in since mid-March. Select doesn’t sell like it used to, but the other sites are a cross between a roulette wheel and a wasteland. I’m growing restless and disillusioned, so I’m going to go exploring. I don’t know what you should do, but I’ll report back with anything interesting I find along the way.

Last time I looked at Amazon’s current algorithms, I speculated what would happen 30 days after Breakers‘ giant free run. At that point, all the free copies it gave away would stop counting towards its rank on the popularity lists. That was a frightening prospect, but at the same time, I’d racked up some 2300 paid sales (and another 600 borrows) in the 30 days since my giveaway. Would those be enough to sustain my place on the pop lists? If not, what would happen? Would I face a slow decline, or a swift one? Would I stroll down a hill, or smash down a cliff?

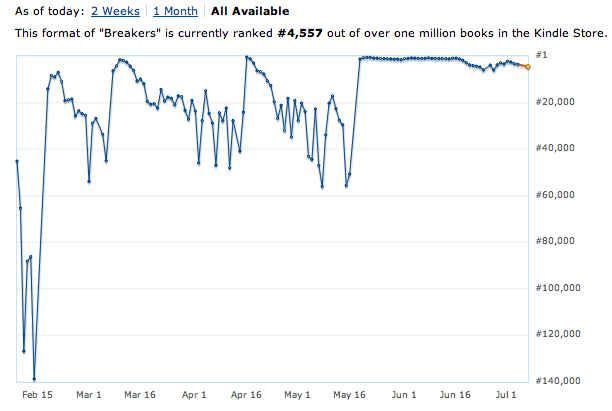

Well, here’s a look in chart form. Here’s Breakers‘ entire sales history:

|

| Pictured: D’oh |

That doesn’t look so bad. That nice, flat line goes on forever and ever. It’s just a little jagged there at the end is all. Wait, let’s take a closer look:

|

| Pictured: D’oh, Part 2 |

Okay, that’s a better look at what happened. What we’re seeing here is twofold. First, notice that downward slope starting around June 16? That’s when my free days stopped counting. The descent was swift–nearly 1000 ranks a day until I hit #4000, when the decline slowed. That is not a gentle hill. That is a brutal cliff. The drop from #1000 Paid to #2000 Paid is the difference between roughly 70 sales per day and about 40 sales/day. And rank declines more slowly than it rises, meaning my drop was even stiffer than that. Within a week of my free days beginning to roll off, I’d dropped from #1000 to #5000. In terms of daily sales, that was a drop from 50-70/day to 10/day.

I had braced myself for it, but it’s hard to brace yourself for a freefall. Mostly what happens at the end of the cliff is a puddle composed of you.

“But wait,” you say. “Bottoming out at #6000 isn’t so bad. That’s a pace around 500 sales/month. And anyway, rank spiked just a few days after that, taking you back to #2000. What are you bitching about?”

What am I–? Look, we’ll get to that in a moment, Captain Impatience. First, I want to talk about the why some more. Why such a steep decline? After all, my bestseller rank was still really good. #1000 overall, which was something like #8 in Technothrillers and #22 in Science Fiction > Adventure. That’s quite a bit of visibility, isn’t it? And what about also-boughts? At that point, I had a lot of popular sci-fi books pointing back to Breakers in the form of the “Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought” lists.

Well, it turns out those things just aren’t all that important. Ha ha! That is way too flippant of an answer. Totally misleading. In truth, bestseller rank and alsobots clearly matter to some degree, but the more I do this, the more dismissive I am of them in general: while they certainly help generate sales, the bestseller lists are so volatile your book can sink extremely rapidly, and the alsobots are such a harsh filtering process (basically, your book needs to be on the first page of a book that has just been finished by a reader who is interested in buying another book right now) that they are of limited use. I think if you have a very high bestseller rank, or first-page placement on the alsobots of a very popular book, then that can do a lot for your sales, but otherwise, those are the supporting cast to a book’s sales, not the star.

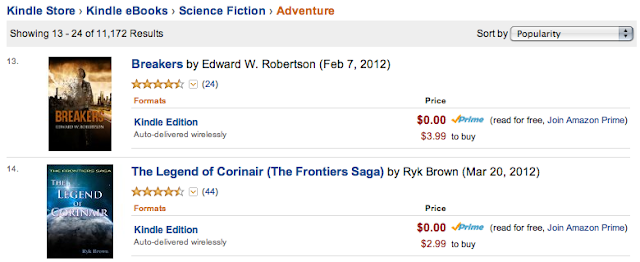

The star is the popularity lists. And your book isn’t on just one of them, it’s on a bunch. For instance, one of Breakers‘ category paths is Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > Science Fiction > Adventure. Each of those is a separate popularity list, which means the book is listed (somewhere) on each of them. Say it’s showing up at #20 on > Adventure; that would place it somewhere around #40-50 in > Science Fiction, and somewhere like #1200-1600 in > Kindle eBooks. In terms of discoverability, it would be very easy to find in SF > Adventure (second page), pretty easy to find in > Science Fiction (page 4-5), and totally awful in > Kindle eBooks (page 100+). No one is going to click through 100 pages in the eBooks category to find it. But this is part of the reason mega-popular books like 50 Shades of Grey or The Hunger Games stay so sticky for so long: when you’re #1 in the store, everyone sees you every time they visit Amazon. Plus the whole “world-destroying word of mouth” thing. But extreme visibility in high-traffic categories leads to a lot of clicks on your book, which in turn generally leads to a lot of sales.

That’s essentially why Select free runs used to do so well on the old pop lists. And that’s why taking a sudden tumble from, say, #10 in > Science Fiction (where I peaked)–the first page of the entire category–to #40-50 or wherever makes such a big difference. And remember, you’ve got another subcategory you’re listed on, too. Once your visibility is lost when a big free run rolls beyond the pop list window, you’re not going to regain it without another push.

|

| Breakers’ peak rank on the Science Fiction popularity list a week before I ate cliff |

As the headline says, I’ve been interviewed at Up Your Impact Factor, a blog about getting by in modern times. What do we talk about? Well, the changes to Amazon’s algorithms, of course, as well as what it means for Select.

Yesterday, Joe Konrath and Blake Crouch put up an interesting post on Amazon’s Select program. The gist is that, with the emergence of viable alternative ebook stores besides Amazon, staying exclusive to Amazon by participating in the Select program is no longer worth it.

I’d qualify that a bit: staying exclusive to Amazon is no longer worth it for bestselling authors J.A. Konrath and Blake Crouch.

I’m sympathetic to their message. For 98% of participants, Select is no longer as powerful as it used to be. It doesn’t rack up the sales like it did just a few months back. Meanwhile, over the last couple years, Amazon’s share of the ebook market has decreased from around 90% to 60% or less. Still huge, in other words, but the other stores are no longer irrelevant. To put it in perspective, let’s look at a completely hypothetical example. Say you’ve got a book that will earn $300 through Amazon each month. Back when Amazon had 90% of the market, you’d only expect to earn another $33 by distributing to all the other stores. These days, having it available everywhere would make you another $200 per month. In an environment where gaining the perks of Select only means giving up 10% of the market, it’s a pretty easy call. When that exclusivity means giving up 40%, it’s a completely different story.

Blake illustrates this by his experiments with Barnes & Noble and Kobo. By enrolling in the Nook First program with his latest book, Eerie, he was able to sell 1500 books in a month of exclusivity–pretty good. Far better than he would have done for the Nook without the advertising and placement B&N gives its Nook First authors.

With another book, Kobo offered him a real promotional flurry–“email blasts, coupons, and prominent placement on their landing pages”. He didn’t have to go exclusive with them, and he was still able to hit the top 10 on Kobo. That month, his Kobo earnings on that title nearly matched what it made on Amazon.

This sounds really good. Much better than the dwindling returns of Amazon Select. But then again, of course it sounds good: this is Blake Crouch we’re talking about.

Blake Crouch can get into Nook First. Blake Crouch can get a massive advertising push on Kobo. Can you? Without those resources at your disposal, how do you really think you’ll do on the other stores? Better than you’d do than if you stayed in Select?

This doesn’t mean I think Select is still the end-all and be-all in the indie world. Kobo is very interesting, and some people do well on B&N. Despite my recent success with it, I’m growing increasingly disenchanted with Select myself; a week back, I scheduled a two-day free run for Breakers that had a good shot restoring its sales, but the promo didn’t begin until 2 AM on the second day. I emailed, called, and emailed Amazon again to reschedule my lost free day for the following day, but they didn’t respond until it was too late. The giveaway went decently, but without that second day, it didn’t do nearly as well as it would have. I gave away some 5600 books; with another day, I probably would have done 8-9K. In my position, that could have been huge. Amazon’s slow customer service cost me hundreds, possibly thousands of dollars.

Guess who’s pretty interested in Kobo and iTunes right now?

But I’m still not pulling everything from Select right away. I have a plan for one of my books that hinges on what Select offers. Select can still help that book better than anything I’m aware of through iTunes, B&N, and Kobo put together.

We’re not all Blake Crouch. I’d like to be Blake Crouch. It would be much easier to make these kinds of decisions when the other stores are willing to put so much marketing muscle at your disposal. In the interest of full disclosure, the only reason I’m leaning toward pulling one of my books from Select is I’ve had an offer–at a much, much smaller level–that would provide it with some visibility there. That, combined with my growing disenchantment with Select, makes me inclined to experiment.

The bottom line is very much a matter of common sense: if Select isn’t getting you much in the way of results, you should totally try the other stores and see what happens. Experimentation is key. You have to fail and fail and fail until you find what works. But if Select is helping, even modestly, or you have a strategy to make it start working for you, then you should probably stay exclusive for now.

Blake gets at that in their post, actually. He concludes by saying that he doesn’t have definitive answers, that the real answer is to experiment and adapt–but Joe pushes harder against Select. He no longer thinks exclusivity is worth it.

Well, maybe not for him. But it still might be for you.

In my last post examining the effects of a large free run under the current algorithms, I looked at how Breakers‘ sales had been in the week after giving away 25,000 copies. They looked steady. And given that the book would have very strong position in the popularity lists for 30 days, my best guess was that sales would stay strong throughout that period.

Still, that was just a guess. And I thought it was also quite possible that sales would slow. Significantly so, even–maybe regular browsers of the popularity list would all snap it up in the first few days, leaving it much more sluggish after that. There was no way to know for sure until more numbers came in.

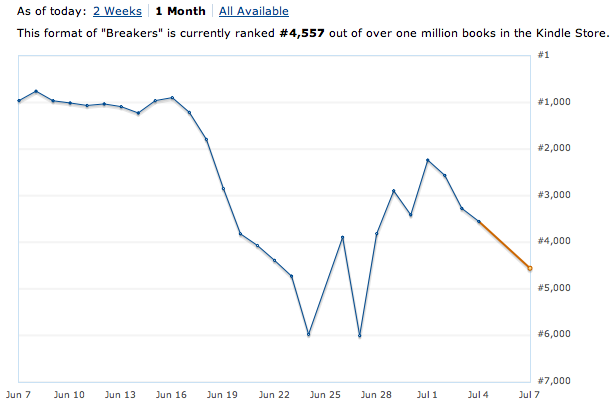

Okay, by my count, it’s now been 17 days since Breakers reverted to paid. Here’s a look at its last 30 days of sales:

That is a line. An almost-straight one. That line represents numbers that are frankly humbling and my-mind-blowing; I’m not sure how to address this without it coming across as bragging. That line represents some 1250 sales and 400 borrows.

Yet it’s also a bit deceptive. That graph is measuring all numbers between #1 and #60,000. How does it look at a more micro level? Here’s the graph for the last two weeks:

By Authorcentral, it peaked May 22, ending the day at #550. It declined every single day after that, reaching its nadir at #1583 on May 31. On June 1, it leapt to #1099; it reached #821 by June 3, and while that graph isn’t showing its latest increase, at 12:45 PM June 5, it’s at #852.

What caused the rebound? Borrows are a big part of it. Breakers has been listed at #1 in Science Fiction in the Kindle Online Lending Library for at least a week now. Despite the top placement in its genre, in the last four days of May, Breakers had 37 borrows, averaging 9.25/day. In the first four days of June, it’s had 110–27.5/day. Clearly, most Prime members had exhausted their monthly borrows by the end of the month; as their borrow refreshed June 1, many new readers snapped up the book.

But an extra 18 borrows a day isn’t quite enough to boost it from #1600 to #800. The borrows can be explained by the start of a new month, but raw sales are also up, too, from 57.75/day in the last four days of May to 77.5/day over the first four days of June. That’s a 34% increase(?!?).

How to explain that? I don’t know. Its pop list ranks have been steady for days now. Presumably, as borrows came in, boosting Breakers‘ rank on various bestseller lists, the additional visibility led to a few more sales, but I don’t think that’s the only–or even the primary–driver of these extra sales. Its bestseller ranks haven’t rebounded that much. All I can offer on this front is conjecture: Are shoppers more free with their money early in the month? Does Amazon send out extra recommendation emails at the start of the month? It’s also gotten 23 new reviews since going free (it had just 9 before); is that helping to convince shoppers to click “buy”?

I don’t know. All I can conclude is that a free giveaway can pay off heavily in borrows as well as sales–right now, Breakers is #12 on the popularity lists in all Science Fiction, but none of the books above it are enrolled in Prime, meaning it gets the #1 spot in the KOLL. The frenetic pace of early-month borrows is already slowing, but that was a nice shot in the arm–my sale : borrow ratio is currently at almost exactly 3 : 1. I believe very few of those borrows are cannibalized sales. My gut feeling, having seen numbers on a bunch of other books, is that a more “normal” sale : borrow ratio would be more like 10 or even 20 : 1. In other words, a full ~25% of my total income so far this month is directly due to having such ridiculously high placement in the KOLL.

17 days in. That gives me another 13 before my free downloads slide beyond the 30-day window of the popularity lists. In another two weeks, then, I expect the gravy train to run out of steam. Possibly to fly off the rails altogether. But it won’t vanish from the popularity lists altogether–by then, it’ll have somewhere in the neighborhood of 2000 sales credited to its ranks, meaning it might only drop from page 1 to page 2 or 3. Even so, that could lead to a death spiral, a negative feedback loop where lower visibility –> lower sales –> even lower visibility –> even lower sales, but we’ll see.

Wherever it goes from here, I can’t consider this as anything but a success. It’s been fascinating to watch, and from a personal angle, it couldn’t have come at a better time–my fiancee’s workplace is reducing everyone’s hours, and our ability to scrape by, already rocky, might have become downright jagged. Even if it crashes and burns in another two weeks, it’s already saved our bacon.

So we’re now three weeks into Amazon’s most recent set of algorithms. I don’t know the first thing about what they’ve meant for the overall activity of the Kindle store, but in terms of books in the Select program and free giveaways, some trends are starting to emerge. And they generally aren’t too favorable.

Yet they aren’t completely disastrous, either (depending on your definition of “disaster,” anyway). Phoenix Sullivan has a week’s worth of data on ten different titles showing a 500% increase in income in the week after her most recent free runs. At the same time, she sees that it now takes a significantly higher number of downloads to see increased sales.

Over at the Kindleboards MEGA-THREAD devoted to the tracking of free data, results are kind of all over the map, but show persistent evidence of decreased post-free sales. (Link goes to results posted after the May 3 changes; when browsing, make sure to look for free runs that took place after that date.) Still, it’s also showing that post-free sales haven’t dried up completely. Meanwhile, Russell Blake, who’s been doing pretty well for himself in part due to free runs and is touch with a bunch of other authors, has mentioned post-free sales are only about 10% of what they used to be back in the glory days. In the episode of the Self-Publishing Podcast I was on, Johnny B. Truant mentioned he’d recently given away 8000 copies and seen no appreciable sales bump. After what Phoenix has termed the Golden and Silver Ages of Select, these diminished numbers are fairly discouraging.

But here’s something else that appears to be a part of the new system:

This is Breakers‘ entire sales history, dating back to its release on February 7. Now let me doctor the charts a little bit:

The two red bars mark the approximate dates of algorithm changes. 0, 1, 2 all fell during the days of List A; 3 took place during the days of List A/B/C; 4 is what we’re seeing with the most recent set. 0 was the release date. 1, 2, and 4 came after free runs. 3 was an ad/sale price promo.

The pattern’s pretty clear, right? Under the old algorithms, books would peak, then gradually decline over the next few days until they returned to Spiky Land, where sales are few and inconsistent. (My Spiky Land sales rate was generally 0-6 per day.) The trajectory looked like the flight of a lofty home run ball in reverse–a swift rise, then a steady downward slope. Since my latest free run under the new algorithms, however, the sales trajectory is more like.. the path of a torpedo. A sexy torpedo. One that doesn’t show any major signs of slowing down.

For another three weeks, anyway, which is when things will get really interesting. What’s happening here is this. Breakers gave away 2.5 shitloads of books on its last free run (where a “shitload” is defined as 10,000 copies–note that we’re using customary measurements, not the Imperial scale). Right before it was free, its popularity list rankings were #121 in Thrillers > Technothrillers and worse than #500 in Science Fiction > Adventure. Where is it now?

Technothriller isn’t the biggest category in the Kindle store, but SF > Adventure is a pretty tough one. This is the category where George R.R. Martin and Wool chew everyone else up and drool them down their sales-fattened bellies. Yesterday, Breakers was actually #12–page 1!–but a new release from Amazon’s 47North imprint vaulted ahead of it today.

Here’s the difference between the old algos (List A) and the new. When Breakers came off free, it would have vaulted to #1 in both categories. It probably had enough downloads that it would have hit page 1 of the entire Mystery & Thrillers genre. This would have produced a rush of sales (almost certainly hundreds), but after a few days, its rank would start to decay. It would get leapfrogged by the latest post-free books off big runs of their own. Within about a week–maybe two, given a giveaway of this magnitude–it would probably be back down near its former rank and sales.

If anything, the opposite is true now for big giveaways. Initially, Breakers hit Technothrillers at #12 and Adventure at #27. It hadn’t sold much over the 30 days prior to being free. 110ish copies, I think. The new pop lists look at a 30-day rolling window of sales. Once it reverted to paid, then, its pop list placement was calculated based on 25K freebies + 110 sales. But since its free run, it’s been selling 70+ copies per day. As the 30-day window advances, then, last month’s low sales days are discarded from the equation while its most recent high sales days are added to it. The result: it has steadily climbed the pop lists ever since.

By now, it’s probably about peaked. And in another 3 weeks, those 25K freebies will roll beyond the window. At that point, it will drop down the pop lists again. How much? That will be determined entirely through how many copies it sold over its new 30-day window. But if that arrow-straight sales line from its sales history holds out, we’d be talking somewhere in the neighborhood of 1500-2000 copies–in other words, enough that it’ll probably still be somewhere on page 1 of Technothrillers, and probably page 3 of SF > Adventure. That would still be a lot of pop list visibility.

In other other words, it could get sticky.

Assuming the algos don’t change over that time, of course. And that I don’t get 50 consecutive one-star reviews. And that the collective unconsciousness doesn’t decide Breakers is 300-some pages of garbage and that its author should be defenestrated with all possible haste. Or that interest doesn’t simply dry up. The U.S.S. Me could be torpedoed at any time.

Back to the big picture. In general, Select is no longer as effective at generating sales as it was just last month. The visibility produced by most giveaways is much lesser than it was before. But if you get lucky enough, that visibility will last for much longer. More visibility, more sales. While in most cases, Select is the least useful it’s ever been–and part of me isn’t happy about that at all–in certain instances, it’s become a more powerful tool than ever.

I’ve made a small edit to my first post on Amazon’s recent changes to their sales algorithms. As you’ll recall, in that post, I took a look at the three different sets of popularity lists Amazon was displaying between March 19 and May 3. To summarize, List A was Select- and indie author-friendly. List B showed signs that making your book free would be drastically less effective than it used to be. And List C looked downright draconian: even strongly-selling indie books that had never been free were ranked 15-25% worse on List C than on List B.

Originally, we thought this was because List C factored physical book copies into its ranks, inadvertently penalizing indies who predominantly sell ebooks. We were wrong. The difference appears to be about price.

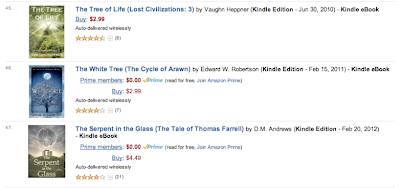

I first started looking into this after Phoenix Sullivan noticed there were very few $0.99 books high on the popularity lists. (The popularity lists are the main browsable lists displayed on Amazon. For instance, the Epic Fantasy list can be seen here.) It was theorized that the new algorithms were discriminating against the $0.99 price setting, weighing $0.99 sales at a lesser value than at higher price points. I wasn’t entirely comfortable with this theory, because I generally don’t think Amazon sets their algorithms with specific goals in mind (besides “Make $, win”). So I compared hundreds of books on several different popularity lists, focusing on the lowest-priced ebook titles. Soon, I was honing in on the highest-priced books, too. Because I was seeing something very, very strange.

The higher the price, the better the book was placed on the popularity lists.

In other words, say you’ve got a $0.99 book at #10 on the Epic Fantasy list. (Popularity list, not bestseller.) Say its sales rank (bestseller list) is #1000. The books at #9 and #11, meanwhile, are both listed at $9.99–and their sales ranks will probably look more like #3000, say.

This isn’t an ironclad correlation. Bestseller rank is a transitory thing. It shifts very quickly compared to popularity rank; a book that’s #1000 today could be #1 or #10,000 tomorrow. Seeing one instance of a book outperforming its bestseller rank on the pop list ranks proves nothing.

Seeing hundreds of these instances, however, is another thing altogether.

And that’s what I saw. Repeatedly. Undeniably. It was 1 AM, I’d had a couple of drinks, and my fiancee was snoring on the couch as I nerded it up with my numbers, but what I was seeing was strong enough to not only prove the theory I’d set out to disprove, but to go one step further: all things being even in terms of sales, not only did a lower price indicate a worse position on the popularity lists, but a higher price indicated a better one.

The implications for indie authors are immediate. And not pleasant. Most indie authors price their ebooks between $0.99 – $5.99. A few brave souls and small presses price as high as $9.99, but generally speaking, $5 and under is seen as the way to reach readers who may be hesitant to take a shot on a lesser-known or completely anonymous author. But if you price at $2.99 while HarperCollins prices at $12.99, you’re going to have to sell significantly more copies to be neighbors on the popularity lists. And if you’re selling at $0.99, you’re going to have to sell very, very well to achieve the same level of visibility.

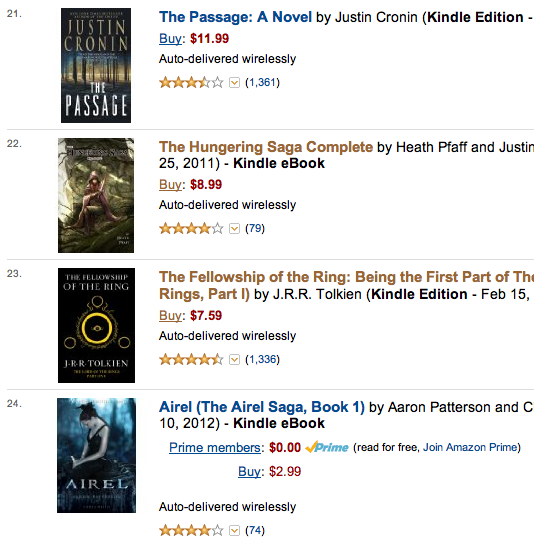

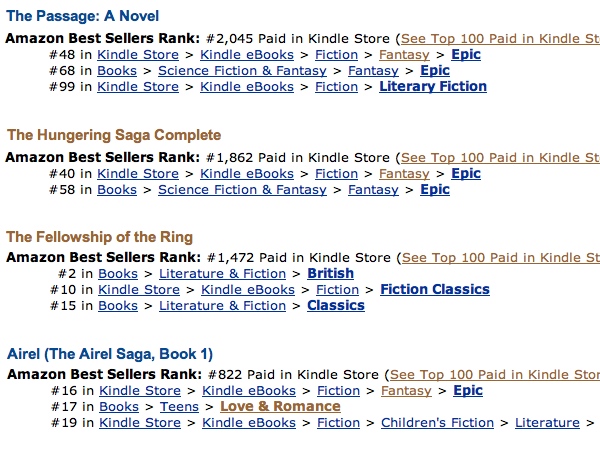

We’ve termed this change “price biasing.” Here’s what it looks like in practice. Let me show you a shot of the Epic Fantasy popularity list:

|

| Evidence of price biasing: Epic Fantasy popularity list, page 2 |

Now, here is the bestseller rank of these same titles:

|

| Bestseller ranks of these same books |

Let’s move to the next page:

|

| Epic Fantasy popularity list, page 3 |

And their bestseller ranks:

|

| Bestseller ranks of these same books |

Take a look at that–in the first example, all of the higher-priced books shown are ranked above the lower-priced books on the popularity list, but their sales ranks are worse. In order! In the second example, the $0.99 book requires drastically higher sales to keep pace on the popularity lists with the $13.99 book. For another example of price biasing, simply go to the top of Epic Fantasy, where George R.R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones 4-Book Bundle, is priced at $29.99 with a bestseller rank of #60 and a popularity list rank of #1. The next book, Martin’s A Game of Thrones, is priced at $8.99, yet is #2–behind the omnibus–despite a bestseller rank of #27.

There are a lot of variables at play here. Because of the volatility of bestseller rank, I can’t be certain that the higher-priced books haven’t outsold the lower-priced ones over the last 30 days, and it will be easy enough to find counter-evidence where books are “properly” ranked and price seems to make no difference. But I’ve tried to minimize the variables by choosing books that haven’t been recently released (so sales should be steadier) and by going to page 2 and 3 of the popularity list, where the volatility should be lesser than at the very top. Really, it wasn’t hard to find this example. Because it’s all over the place. And if you look at hundreds and hundreds of titles next to each other on the popularity lists–especially the extremes, $0.99 – $2.99 books next to $12.99 – $29.99 books–the correlation is extremely high.

I don’t have the answers to a lot of the inevitable questions. I don’t know what the “ideal price” would be to take advantage of this new formula. I don’t know how many more copies you need to sell at $0.99 to achieve the same weight as you would selling at $9.99. I don’t know why Amazon did this, particularly when they price their own imprints at $7.99 and under. I don’t know if this is the end of the world or a brief couple weeks of suffering followed by another golden age.

And let’s not storm the gates or raise all our titles to $199.99 just yet. The popularity lists are far from the only driver of sales through Amazon. There are bestseller lists. Targeted emails. Bargain book lists of all shapes and sizes which you’ll only make through pricing lower. And if you raise your prices significantly enough to achieve a major change on the new popularity lists, you may drive away so many sales your placement actually winds up going down. Unless you’re priced at $0.99, I don’t think raising your price by a dollar or two will make any real difference to your placement on the popularity lists, so please don’t overreact–if you’re still selling, you’re still selling, no matter how the new algorithms may work.

Still, I don’t see how these new lists are any good for indies under any circumstances. What they do is force us to sell more books to maintain the same visibility as higher-priced trad titles. They diminish our ability to experiment with lower prices, whether the goal is a temporary sale, a low-priced entrypoint to a series, or because you just don’t feel comfortable charging more than $0.99 for that 5000-word story.

Furthermore, the playing field is no longer level. Indie authors published through KDP only earn 70% royalties at prices between $2.99 and $9.99. Yet many traditionally published books that are most benefiting from price biasing are priced at $12.99 – $14.99, with some omnibus editions priced as high as $22.99 – $29.99. If indies want to match those prices to match their visibility on the popularity lists, they’ll actually make less money with each sale than they would at $9.99. There’s no way to win.

I don’t like fearmongering. But I don’t see how it helps to sit on this information any longer. I encourage you to look at the popularity lists for yourself. Maybe I’m wrong. I’d prefer if I were. I’ll try to answer any questions in comments, but be prepared for a lot of “I don’t know.” All I know for sure is that if this analysis is correct, the deck has been stacked against us. I highly doubt it was intentional. Indies aren’t being targeted. We’re just a small part of the Amazon equation, and as Amazon attempts to maximize their revenues, I really don’t think they care who that revenue’s coming from. And remember: this is just one factor among many, many others as to how a book is seen on Amazon’s storefront. It’s not a revolution in and of itself.

But it does feel like it will have some impact on indie authors. I thought it was time to share and let everyone experiment for themselves.

So not 12 hours after my post about how Amazon’s algorithms work, Amazon changed their algorithms again. This is a big enough deal they apparently just caused me to quote Britney Spears.

Fortunately, the latest changes weren’t a complete revolution. By all accounts, there is once again a single list seen by all customers. I’m not sure exactly how this new list works–the Avengers are still working on it–but it seems to hew very closely to one of the lists we already understood. And if you are a Select author who leans on free giveaways for sales, here is my current advice to you:

Sorry, couldn’t resist. I actually don’t think we should flee the battlements just yet, for reasons I’ll get into lower down, but this is bad news for Select authors. Phoenix Sullivan has alluded to this, and will surely have more to say herself, so keep watching. Anyway, cause for panic: the new list looks an awful lot like List B. As a refresher, here are the main mechanics (that I am aware of) for how List B works:

- Ranks are determined by the last 30 days of sales, with no extra weight given to the most recent sales

- Free book downloads are discounted heavily–maybe as little as 10% the value of paid sales

- Borrows don’t count as sales

I’m not sure about whether borrows count or not on this new list. Won’t have the data on that front for a while. I am positive free books are counted, and that they’re counted at a discounted rate–feels like 10-15% of a sale. (In other words, for every 10 freebies given away, you’re credited with 1 sale for the purposes of pop list rank.) You can see this for yourself by trolling the popularity lists. You’ll see a few titles that are permanently free scattered across the first few pages. If freebies didn’t count, you wouldn’t be seeing them on the lists at all, and if they did count, you’d see a lot more permafree titles and Select titles higher up on the lists.

Also, if a book has fewer than 30 days of history behind it, as in it’s a new release, that doesn’t seem to be counted against it. Seems like the pop lists will just count however many days it does have on its record.

What does this mean, then? Well, for starters, it’s probably the end of the 3-day bump. This was the term coined on Kindleboards for sales on Select titles that had recently been free. In the past, List A would update roughly 40 hours after your book reverted to free. It counted freebies to sales at a 1:1 ratio (or very close to it) and weighted a book’s last few days of sales very heavily. So if you went free and gave away 5000 books, in the afternoon two days after your promo ended, your book would be credited with 5000 sales, vaulting it to the top of the “most popular” lists. With your book in front of so many customers, you’d see a lot of sales, spiking late on Day 2 and carrying through Day 5 or so as your rank decayed and your book was pushed down the lists by new titles rolling off free.

I don’t think that’s going to happen anymore. For one thing, List B isn’t weighted toward your last few days. It seems to take an average of your last 30. That levels the playing field for books that have been selling steadily for the last month while largely ignoring sales spikes that don’t prove to be lasting. For another thing, when you come off a giveaway of 5000 books, you’re no longer credited with 5000 sales towards determining your pop list rank. Instead, you’re credited with something more like 500. Possibly 750, or even 1000–I’m not sure just what the conversion rate is–just that it’s definitely a lot worse than 1:1.

If you don’t get credited with sales, you won’t vault up the pop lists. If you don’t vault up the pop lists, you won’t be seen by customers. If you don’t get seen by customers, you won’t sell books.

Does this mean those of us in Select should flee from the incoming flood of orcs? Perhaps. Everyone loves a good stampede. But even if the three-day bump has departed for the swift shores of Valinor, freebies aren’t worthless. Giving away a whole bunch of books still means you’ve got your book in the hands of a whole bunch of readers. I hear word of mouth is a thing. While your book’s free, you’ve got tons of attention, meaning some of that attention will bleed over to your other books–especially if it’s a series. If you don’t have a built-in fanbase eagerly awaiting your next release, it might be a viable strategy to put it in Select, make it free right away, and get it some alsobots to help prop up early sales and build a little bit of what the kids call buzz. Furthermore, if you give away just an amazing amount of books, it may still be enough to pull you some decent visibility. Even if you can’t make page 1 of the pop lists anymore, there would be value in using freebies to push yourself up to page 5.

Also, this is just how things look right now. As should be obvious, Amazon changes how they do things all the time. They are wise. They want to make money. If they still want Select to succeed, at some point they will do something to help it, either by changing the algorithms again or by adding new perks to the program. What we’re seeing now will probably be completely irrelevant in another month or three or six.

It should further be noted that I don’t have the algorithms worked out to a T. I know what I’ve described here is incomplete. With the help of the Avengers, I hope we’ll know more soon, but let me stress this: I don’t know everything. I could be wrong about some parts of this or about all of this. I could be a brain in a jar dreaming that Amazon just screwed me!

But I’m pretty confident about what I’ve laid out here. Confident enough to make it public. For those of us who’ve been leaning on Select to sell books, the next few weeks or months could be lean ones. Plan accordingly.

UPDATE: The same day I posted this, Amazon changed their sales algorithms again. This post will provide a lot of the background to what I talk about in the followup post.

BACKGROUND

Around March 19, Amazon changed the way they sell books. In a Kindleboards thread devoted to the subject, authors tracking the performance of books during and after a free promotion began reporting strange results. Prior to then, books that gave away several thousand copies during a promo would shoot to the top of the popularity lists some 36-48 hours later. It was like clockwork. Clockwork that paid you several hundred dollars.

Because the popularity lists are a big deal. These are the default book listings you’ll see when you’re browsing around by genre. Here’s the Fantasy list, for instance, with GRRM clogging up the top 10 like the greedy goose he is. If you could ride a free promotion to the top of those lists, your book would be extremely visible to shoppers. Depending on genre and your book’s presentation, topping the pop lists could snag you dozens or hundreds of sales before other books overtook you. Sometimes that visibility was enough to launch a book into the stratosphere, where the stratosphere is also made of money. It was kind of a big deal.

Then, things changed. Except they didn’t change. Not for everyone. Authors began reporting lower sales than expected as well as strange-looking lists. Chaos reigned! Dogs and cats living together, watching couch-bound authors tear out their hair. After a couple weeks, we thought we had it figured out: there was no longer a single popularity list. There were two, and books no longer seemed to be vaulting to the top no matter how many free copies they gave away.

Well, we were wrong. There weren’t two lists. There were three.

Because I am extremely imaginative, I’m going to refer to them from here on out as List A, List B, and List C. I’ll get into the methodology in a bit, but for now, I worked this out through carefully observing my books, reading other Kindleboard authors’ results obsessively, and lobbing theories around with other authors. I would never have figured this out on my own. I know, never say never. Trust me, eventually I would have gotten frustrated and left to play Mario Kart instead. One other author in particular did tremendous heavy lifting. Like the Eye of Sauron, he (or she?!) is far-seeing and awesomely powerful. And much like Sauron, you can’t invoke his or her name without facing terrible wrath. Some of the Eye’s secrets must remain just that.

But the outcome of that info can be revealed. So without further ado, here’s how the three lists work.

THE CHANGES

List A is the same version of the pop lists that existed prior to March 19. It is Select- and freebie-friendly. Here’s roughly how it works:

- Ranks are heavily weighted to the last few days

- Free book downloads are weighted equally with paid sales

- Borrows count as sales

List B appears to be a throwback pop list, one that was running throughout most of last year. Here’s how book ranks are calculated on it:

- Ranks are determined by the last 30 days of sales, with no extra weight given to the most recent sales

- Free book downloads are discounted heavily–maybe as little as 10% the value of paid sales

- Borrows don’t count as sales

List C is a lot like List B, with a couple major differences:

- Free book downloads aren’t counted at all

- Recent sales are weighted somewhat more heavily than List B(?)

- Borrows don’t count as sales

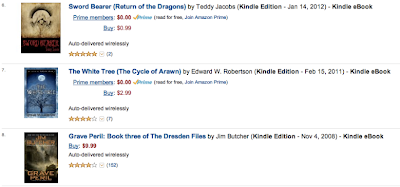

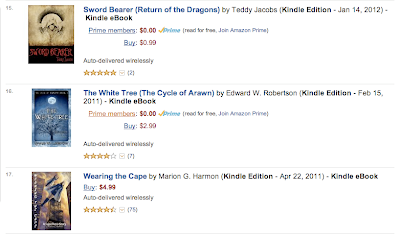

What does that mean in practice? A lot. A lot a lot a lot. Here’s where my book The White Tree ranks on all three lists at this moment in time. Each shot will look a bit different because they’re taken from different browsers–that’s one way to see different lists. The list in question is Fiction > Fantasy > Series, a fairly quiet little fantasy subcategory.

List A:

List B:

List C:

Pictured: Oh shiiiiii–

METHODOLOGY

Most of this was achieved through comparing tons and tons of different books on different browsers, just like the screenshots above. Here’s some stats for the book in question that helped me figure out what was happening here. On March 28-29, The White Tree was downloaded 4700 times (free). On April 17, it was downloaded an additional 1300 times. In April, its paid numbers came in at 210 sales and 46 borrows.

Since March 19, my main browser’s been displaying List B. My big clue to List B came on April 28, when I noticed my book had, over the span of a day or two, dropped from #67 in Epic Fantasy to #165. Rank didn’t slide–it instantly dropped off a cliff. Why? Because it had been 30 days since all those free downloads had come in. I’d noticed the same thing around March 23–I’d done a huge giveaway February 22-23, and once 30 days elapsed, it suddenly plummeted from around #45 to around #255. I didn’t know what it meant then, in fact I don’t think I even knew there were two lists at that point (let alone three), but when it happened again, I had a pattern.

I also had several weeks of observations piled up by then to help me understand new data. For weeks, List B had been showing me very static lists. The books at the stop stayed at the top. There was very little churn. There were very few Select books, i.e. books that were likely to have recently been free, especially within the top ~60 results (first five pages). Most books at the top were traditionally published. List C was even more trad-dominated; generally speaking, an indie title on List B would be ranked 15-25% worse on List C if that title hadn’t been free, and would rank much, much worse if their List B rank was dependent on free downloads (like, hundreds of places).

When I compared the top 240 titles in Epic Fantasy between List B and List C, here’s what I found: on List B, 188 titles weren’t in Select, and 52 were. On List C, 217 titles weren’t in Select, and just 23 were. With no benefit from freebies, and with fewer paperback sales to pad the numbers, most indies get killed in List C.

When it came to figuring out that borrows weren’t counted in List B and C, The Eye of Sauron was particularly helpful. We compared Select books with lots of borrows to non-Select books whose sales were roughly equivalent to the Select books’ total sales+borrows. On List B and C, the non-Select book came out ahead by a good chunk. We compared Select books with lots of borrows relative to sales with Select books with few borrows : sales. (None of these books had recently been free, which acted as a “control” between List A and B.) The ones with a higher ratio of sales : borrows almost always came out better on List B than on List A.

While I wouldn’t lay my life on the line for every one of these observations, I am very confident in the overall conclusions reached. There are three different lists. You can see them for yourself–just compare lists on different browsers, computers, and Kindles. If you’ve gone free recently, you’ll note your popularity rank on List A is much better than B or C.

How do you tell which list you’re looking at? Well, that could take a day or three to figure out, but in short, if you see a bunch of Select titles on the first pages of the pop lists, you’ve probably got List A. If it’s almost all traditionally published books, it’s List B or C. From there, compare your lists on another browser/device; if you’re seeing List C, trad books will generally be even more dominant.

WHAT THIS MEANS

What does all this mean? Hey, maybe you haven’t noticed, but this post is already epically long. The internet is only so big, you know. I’ll save that for a future post. For now, here’s what’s key: there are three different lists. Your book is listed on all three, but any given shopper is only seeing one version of the lists. (In other words, different people see different lists.) If you’re an indie in Select, one of these lists is good. The other two? Well, let’s just hope they’re not here for too much longer.