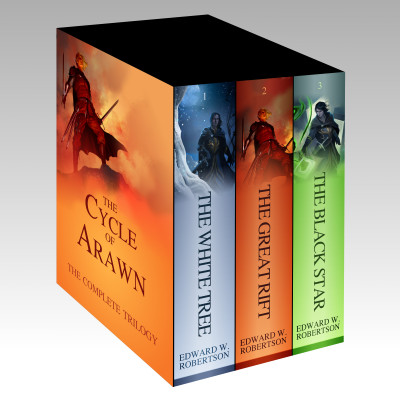

I’ve been reading a lot of agents blogs lately, as much for the insight about the job as to keep up with the reading schedules of the couple I’ve submitted The White Tree to. As useful as getting a degree in fiction was (and I really don’t appreciate the laughter here), the classroom taught me little to nothing about the business side of being a novelist. I knew the basics of why you want an agent and what they can do for you as an author, yeah, but as for the ins and outs–how they work, what they’re like, how you can get their attention–there’s been a constant cartoon question mark floating over my head which didn’t start to shrink until I’d read many thousands of their words.

It’s also helped humanize them. To an inexperience author, agents are a bit like elves, in that they’re elusive and mysterious, and also somewhat like ogres, in that they’re scary and powerful and it’s easy to imagine them reading your query, booming with laughter, then ripping the flesh from a whole shank of mutton before dispatching one of their many crows to caw “Sorry, not right for us” right in your ear.

It’s good, then, to be reminded they’re just normal people. Normal people with the potential to launch your authorial career, yes, but if they say no, it’s certainly not because they’re sadists or monsters. As frustrating as it is to read a rejection as vague as “The story just didn’t grab me” or “I just don’t feel strongly enough about it to be able to represent it effectively,” that’s probably the exact reason they’re passing. (Also, because their schedule’s too full of baby-eating to find the time to work up a proposal for your book.)

So mostly I really like reading what they have to say, and was taken aback when I saw, in more than one place, that agents don’t want to see you talking about getting rejected on your blog. Boy are my ears red!

It’s true that the only thing America hates worse than a loser is a cheater. If an agent sees your book’s been turned down by fifty other agencies, she won’t be too upset to be the 51st. Even Miss Snark said she didn’t want to see you talking about rejection unless it was to reminisce after you’d become a published author, which I found hilarious, in an exasperating way. It seemed to be saying two things: first, that everyone gets rejected at least a few times and often a whole lot of times, but let’s all pretend you’re perfect until you’re too big to be hurt by admitting someone once thought you weren’t worth their time; and second, we’re probably going to turn you down even if we think you’re pretty good (numbers are nigh-on impossible to come by, but one average-sized agency turns down 99.75% of the submissions they receive), but right or wrong, we sure as hell don’t want to hear about it later.

Let me just say that I totally, completely and utterly understand the reasons why talking about rejection is annoying at best and self-destructive at worst. (With the exception of anything and everything I have to say here, obviously.) I’ve read some unagented authors’ blogs and learned just how strong the bitterness is in us ones. Cheaters and losers are the leaders of the Hate Pack, but whiners nip right at their heels.

Nobody wants to read about what a tasteless prick Agent Moron is, let alone one of his colleagues who might have been thinking about asking to see the rest of your book until you’d just expressed the belief all agents are human sewers. A lot of writers take rejection very, very personally, even when it’s a polite and contrite form letter; I’ve read in several places that the fact people are often so angry, defensive, and insulting when an agent or editor offers them constructive criticism is the very reason most of them don’t. Seething and complaining just makes you look like the jerk. Just like James Bond, you’ve got to never let them see you bleed.

Because, you know, it’s not personal. Rejection’s a fact. Nobody likes saying no any more than we like hearing it, but it has to happen. There’s a thousand stories about the writer who was turned down a billion times and today he’s the King of Authoria. A year after his first book came out, everyone loves Pat Rothfuss, but back in the day The Name of the Wind was rejected by every agent in Christendom. (Well, by 25, I think, which is both a lot and not very many at all.) And some day, if the writing’s good enough, someone will take that chance on it.

Flip side of the coin: I’m not sure anyone who hasn’t been through this understands just how rough it is to keep hearing “No.”

I might know I’m the motherfucking bomb, but unless the People Who Matter (i.e. agents and editors) agree with me, my monumental greatness makes no difference at all. The easy answer is to persevere until you find that enlightened arbiter who will slap her colleagues across the face with your manuscript until they fall to their knees in tears and line up to offer you an eighty-book contract. After all: good writing shines through. Keep writing, keep submitting, and eventually you’ll reach the ears of the one person who matters.

But of course art and entertainment isn’t quantifiable. You can’t really know you’re worth printing. Everyone who sends a query to an agent or a story to an editor believes (or at least hopes) they are, but at best you’ve had some friends or your critique group tell you they like your work, which means next to nothing because they sure as shit can’t tell you they hate it, and even if they did you’d just write them off as morons. Before you’re regularly in print, really all you’ve got to go by is the People Who Matter, and if the People Who Matter keep telling you “No,” sooner or later you’re going to reach the conclusion either they’re all crazy and wrong, or–crushingly, devastatingly–you’re just not all that good.

It’s a long wearing-down, an erosion of confidence, the grinding of all outward evidence that says you’re not good enough against whatever’s driving you on to write no matter what the outcome. It’s stress, stress, stress. Stress causes fraying, breaks in your nerve and your cool.

We worry that we’ll sit down on this new novel and give it all the energy and free time we can muster until a year or three later when at last it’s done, and we’ll send it out, and still nobody wants it. That fear’s killed more half-finished novels than all the other time-sucking responsibilities and relationships and real jobs combined. Probably a good thing. Too many of us wannabes as it is.

There’s always the hope that you’re learning and developing, that the next one you write will be the one. I once read a poll on an author’s site asking other authors how many books they wrote before they had one published. For most, it was more than one; for many it was three or four; for some it was six or eight or ten. Sanity’s as hard to quantify as artistic merit, but if you’ve written ten books and nobody’s bought one, that might be a sign. On the one hand, there’s probably not much that can stop someone who’s written ten books from writing the eleventh. On the other, it’s either very hilarious or very sad to consider how many times they’ve heard “No.”

Good art’s kind of like obscenity, but with less risk of ejaculation. You might not be able to define it, but you know it when you see it. With anything you can’t quantify, though, it helps to know someone else has already decided the work in question doesn’t suck. Agents are very right when they say it only takes one yes. People are–and this is usually a good thing–herd animals. If Someone Who Matters gets you that book deal, or prints your story in their universally respected and beloved magazine, that fact alone will make Someone Else Who Matters all the more likely to give you the benefit of the doubt.

Conversely, if Someone Who Matters stumbles on your blog where you admit being turned down right and left, well, good luck convincing them to take you seriously.

So. I know we’re not supposed to talk about rejection. I know it’s unprofessional and unseemly, that insecurity is unattractive. Anyway, it’s almost impossible to talk about it without whining, bitching, moaning, or otherwise making yourself look petty or clueless or deluded. It’s a terrible idea and only an idiot would indulge in it.

But one of the reasons I write–and I really, really doubt I’m alone–is because sometimes I have feelings I can’t deal very well with in real life, but if I translate those emotions into fiction, it makes them a whole hell of a lot less scary. I don’t know that Freud ever really figured out artists, but it’s just another form of repetition compulsion, putting something big and hard to handle in an environment where you’re (more) in control. The idea isn’t to be transparently autobiographical. It’s just that when I write a character who in some way moves through the same emotional territory I have, suddenly the whole thing makes a certain amount of sense. Maybe the place to deal with rejection isn’t the internet, but in fiction. Still: it wears on you.

“Shrug it off and send it somewhere else.” That’s the advice the pros give, both agents and authors. Honestly, it is good advice. Hope springs eternal that Agent Brilliant will see what Agent Arbitrary passed on. And really, in the scheme of things, one rejection means nothing. That individual could just have different tastes, or be in a bad mood, or too busy, or not know an editor who’d be interested, or maybe they really are just a fool without the ability to understand what you’ve got here.

But as the herd gets bigger and the “No” gets louder, it gets harder and harder to ignore what they’re saying. We’re not individuals, we’re sheep, too. We want to be with that herd. All those other guys aren’t saying “No” for their health, it’s because they believe it, and maybe we should stop holding out already and get over to their side of the pasture. But the only thing that hurts worse than constantly convincing ourselves they’re all wrong is starting to believe they might be right.

It’s more of a wading through than a shrugging off. The energy just keeps on coming, which is proof in itself that John Gardner was on to something when he said all fiction should be life-affirming. Today I wrote a movie review. Put this together, for whatever it’s worth. It’s 2:23 in the morning and I’m about to dive into a short story and not stop until sunrise. Tomorrow, I’ll get together some queries for this new draft of The White Tree. The book’s good. People will want to read it. There’s just two more things I need to do: keep going until it finds a home, and try not to be too obnoxious until it does.