And Then Everyone Died

Um, there are going to be spoilers for Cloverfield and The Thing to follow. Really though, if you haven’t seen them yet, renting and immediately watching them would be a better use of your time than reading this.

I’m currently in the middle of writing a story where everyone dies at the end. I know this is a classic no-no; the conventional (and usually correct) wisdom is that killing your characters at the end is a dramatic copout for writers who can’t think of a real ending for their story. It’s a big fat cheat, and the only thing America hates worse than a loser is a cheater. Also, “and then everyone died” is kind of nihilistic. It’s something teenagers write. Nobody wants to write like teenagers, including teenagers.

But obviously there are exceptions. It can be done well. The Thing and Cloverfield are Exhibits A and B. So how come they work when so many other “whoops dead” stories don’t? What makes them so special? Most important of all, what can I steal from them to make my own fucking frustrating almost-finished story work, too?

I think I get The Thing. Kurt Russell and Keith David, the last survivors, are clearly going to die at the end, but it’s not so much that they’re being killed by something as they’re making the choice to die. And not only is it a choice rather than a condition imposed on them, it’s a moral and logical choice: if one of them’s infected, and they live to bring that out into the world, then the world’s toast. Killing themselves/each other is an enormous fucking sacrifice; it doesn’t get much more noble than giving up your own life to preserve the rest of humanity. Oh, yeah, that’s why Danny Boyle’s recent Sunshine worked, too.

Resolved: everyone can die if it’s for a cause.

“Getting eaten by a 350-foot giant fucking monster” is not a cause, yet somehow Cloverfield’s ending feels right and proper. I’ll admit a strong wave of some emotion that translates roughly to “Oh hell no, Hud just died?!? Boo on that,” but that was swept away by that ending, which felt both sad and earned. I guess it was a little more in the Greek tragedy mold, where Rob’s hubris kept him from getting together with Beth until the ending, at which point it was too late to avoid getting bombed into vapor.

Yet again, work gets in the way of what’s important, so I must cut this short. But a lot of what Cloverfield’s about is terror coming from nowhere. It’s senseless and unstoppable. A lot of average people die. In that light, killing all the characters is natural; it’s not really a cheat when the whole point is that, by definition, a tragedy’s something a lot of people don’t escape.

I’d like to claim I’ll be thinking about this stuff a lot tonight, but I envision a long series of procrastinating to Futurama commentaries instead.

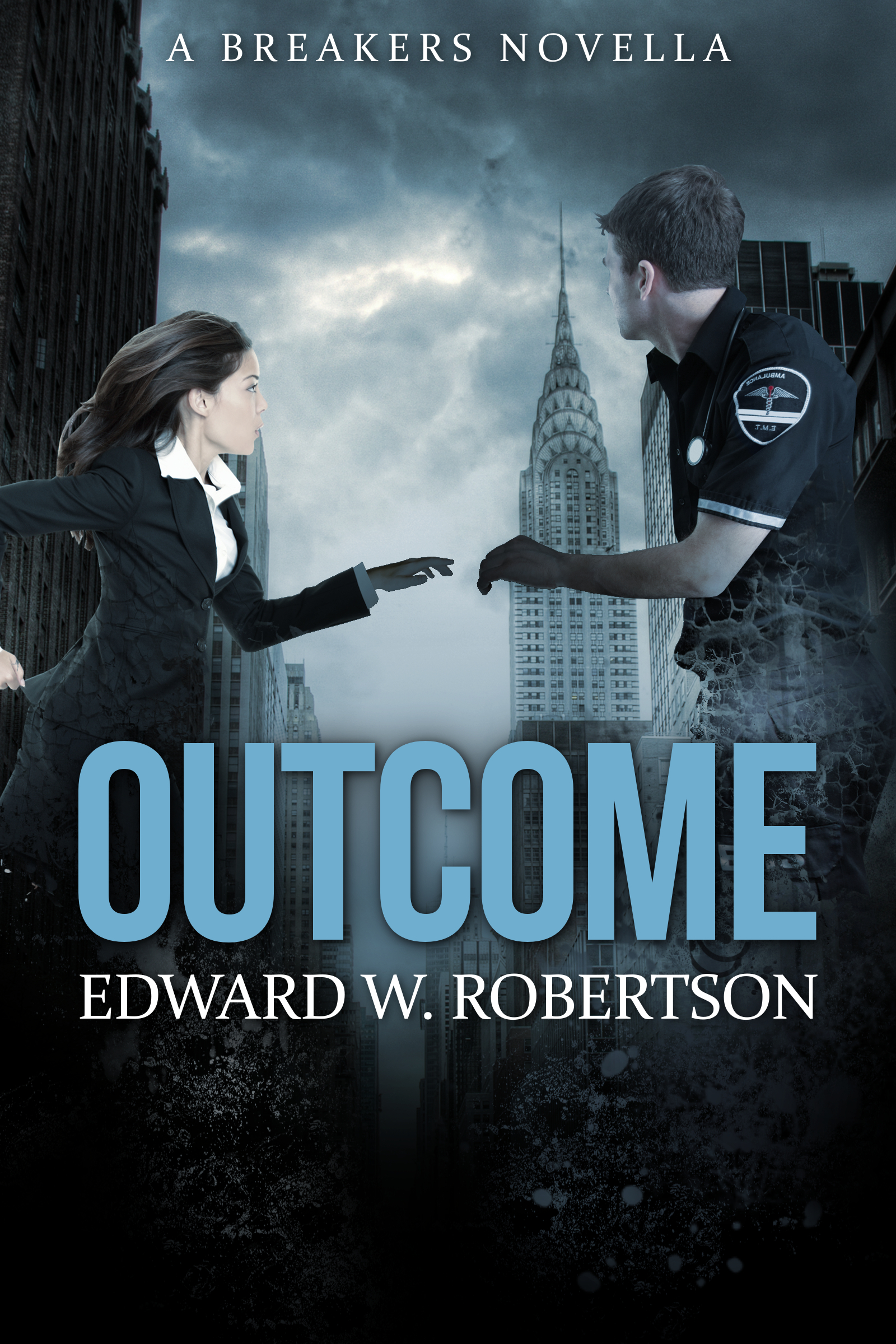

Outcome

As an agent of the Department of Advance Analysis, she's one of a handful of people who knows about the spread of a new virus--one she believes will wipe...

More info →- Fantasy (5)

- Science Fiction (16)

- Breakers (11)

- Rebel Stars (3)

- The Cycle of Arawn (4)

- The Cycle of Galand (1)

Leave a Reply